How the Event Loop Works in Node.js

The event loop is a fundamental concept of Node.js. It opens the door to understanding Node’s asynchronous processes and non-blocking I/O. It outlines the mechanisms that make Node a successful, powerful, and popular modern framework. This tutorial is useful for Node.js developers who want a deeper understanding of what's happening under the hood of every application, and those who want to take full control of every step of its running cycle.

In this tutorial we'll:

- Explain how the Event Loop in Node.js works, as well what actions are being executed during each of its phases.

- Understand Node’s processes and threads.

- Explain the difference between blocking and non-blocking code in Node.js.

- Learn how Node's Event Loop offloads heavy I/O tasks to the C++ APIs.

By the end of this tutorial, you should have a good understanding of what Node's Event Loop is and the role it plays in execution of Node.js code.

Goal

Understand how the event loop in Node.js works, as well as the actions, or "macro-tasks", being executed during each of its six phases: timers, I/O callbacks, preparation / idle phase, I/O polling, setImmediate() callbacks execution, and close events callbacks.

Prerequisites

- None

Terms and definitions

We will use the following terms to help explain the Node.js Event Loop:

Process: the runtime of the application during the execution. The process starts when the application starts execution. It has a dedicated memory pool and can have multiple threads.

Thread: a coding sequence that resides within the process and uses its memory pool.

Call Stack: a stack data structure that holds the information of called functions that allows transfer of the application control from these functions to the main process after code inside the functions has been executed.

Multithreading: architectural concept that allows a single process (application container) to have multiple coding sequences that can be executed concurrently within a single main process.

Memory Pool: a data buffer that is dedicated to the particular process during its runtime.

Tick: the time frame that outlines one full Event Loop iteration from start to finish.

Timer: a function that executes code after a set period of time.

I/O: Input/Output, any task that involves external hardware -- file system, network operations, etc.

Process and threads

Let's dive into the concept of process. Every application has a container. Process is the top-level container of the application. When you run an application with Node.js, e.g. node index.js, you are creating a Node.js process that the application runs in.

Every process has a dedicated memory pool that is shared by all threads in the process. This means you can create a variable in one thread and read it from another one.

To understand the concept better, imagine going to a restaurant that has a dedicated waitress who asks you for your order and takes the order to a chef. While your food is being cooked, the waitress cannot take anybody else's order since they are dedicated to you. This means they are blocked from any other actions! Other customers come in as well, but nobody goes to take their orders, since the waitress is still waiting to serve your food.

The easiest solution to this problem would be to hire more people to take orders. After some time, the number of waitresses would be equal to the number of clients who are dining. This is the classic example of how applications like Apache server process requests where a "waitress" is a thread. Every request gets its own thread. This outlines the concept of multithreading.

This solution may not be memory-efficient due to its dependency on the release of resources and allocation of memory on time. Due to threads sharing limited resources allocated to the application process, creation and release of the resources may result in significant overhead and in turn impact performance.

On top of this, multithreading contributes to software complexity as threads need to communicate between each other to stay synchronized with the main thread and other threads. For example, a thread needs to notify the main thread when an operation is finished.

Multithreading can introduce a "Race Condition", a bug that happens due to lack of synchronization between two threads, and our inability to know which thread will access a shared variable first.

To avoid these complexities, Node.js is single-threaded. This means that all operations execute in a single thread. In other words, Node.js applications have a single call stack.

A call stack operates as a queue. During execution, when an application steps into a function (executes the function), it pushes the function into the stack. When the application steps out of the function (the function returns), that function is removed from the call stack. A call stack records where in the program structure we are at any given time.

In the scenario where a slow, or processing-heavy, function is added to the stack, we cannot move out of it and on to the next function until the current function has finished its execution.

This can cause blocking, and slow execution of the application. While the stack is blocked, users cannot interact with the application as the Node.js runtime has one thread and can only do one thing at a time... or can it?

Behind the scenes, there are C/C++ APIs that provide asynchronous input/output (I/O), and interaction with the operation system (OS), that allow code execution similar to multithreading without the same memory shortcomings. The Event Loop was implemented to assist with the interactions between these asynchronous components and the main application thread. The Event loop is implemented as part of the libUV library that provides cross-platform asynchronous I/O in Node.js.

The Event Loop in Node.js

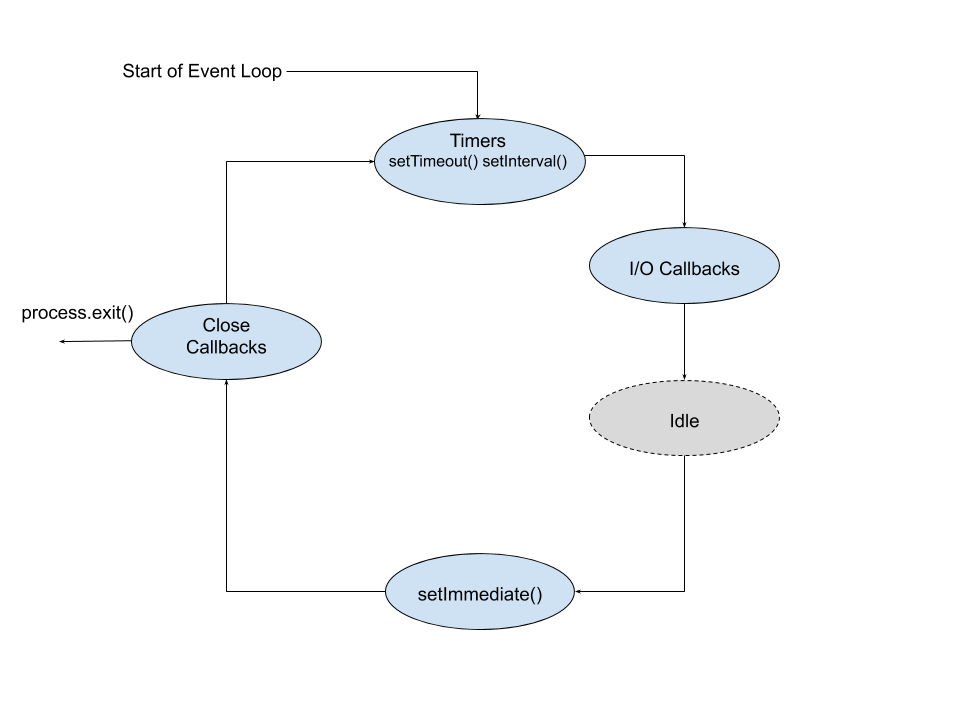

The Event Loop is composed of the following six phases, which are repeated for as long as the application still has code that needs to be executed:

- Timers

- I/O Callbacks

- Waiting / Preparation

- I/O Polling

-

setImmediate()callbacks - Close events

The Event Loop starts at the moment Node.js begins to execute your index.js file, or any other application entry point.

These six phases create one cycle, or loop, which is known as a tick. A Node.js process exits when there is no more pending work in the Event Loop, or when process.exit() is called manually. A program only runs for as long as there are tasks queued in the Event Loop, or present on the call stack.

Some phases are executed by the Event Loop itself, but for some of them the main tasks are passed to the asynchronous C++ APIs.

Phase 1: timers

In Node.js timers, or functions that execute callbacks after a set period of time, are provided by the core timers module. This module provides two global functions: setTimeout(), and setInterval(). These allow you to define code to execute after a period of time.

Both functions take a callback function, and delay in milliseconds, as their arguments. Additional arguments can optionally be passed after the delay -- those arguments will be passed to the callback function.

The timers phase is executed directly by the Event Loop. At the beginning of this phase the Event Loop updates its own time. Then it checks a queue, or pool, of timers. This queue consists of all timers that are currently set. The Event Loop takes the timer with the shortest wait time and compares it with the Event Loop's current time. If the wait time has elapsed, then the timer's callback is queued to be called once the call stack is empty.

Node.js has different types of timers: setTimeout() and setInterval(). The fundamental difference between them is that setInterval() has a repeat flag which places the timer back into the queue once its execution is finished. This is a how a process, like a server, can stay "alive" waiting for a request indefinitely.

The nature of executing timer callbacks as part of the Event Loop explains the non-obvious feature that a timer's wait time is not an exact time in which the callback will be executed -- it is, in fact, a minimum time that will pass before the callback is queued for execution.

Phase 2: I/O callbacks

This is a phase of non-blocking input/output.

To better understand blocking vs. non-blocking I/O, let's revisit our restaurant example. Imagine you're waiting for your food. While the chef is cooking you are unable to do anything else. You can't order a drink, your kids can't draw with the crayons, and you can't discuss your work week with your spouse. You are all blocked -- waiting for the food to come in. When the food finally arrives, you're un-blocked and can continue enjoying the experience. While it is logical that you can't eat without food, it would be silly if you couldn't indulge in some other non-blocking activities while you're waiting.

Similarly, when your application is waiting for a file to be read, it doesn't have to necessarily wait until the system gets back to it with the content of the file. It can continue code execution and receive the file's content asynchronously when it is ready.

This is what non-blocking I/O interfaces allow us to do. The asynchronous I/O request is recorded into the queue and then the main call stack can continue working as expected. In the second phase of the Event Loop the I/O callbacks of completed or errored out I/O operations are processed.

Let's look at a code example:

fs.readFile("/file.md", (err, data) => {

if (err) throw err;

});

myAwesomeFunction();

The fs.readFile operation is a classic I/O operation. Node.js will pass the request to read a file filesystem of your OS. Then the code execution will immediately continue past the fs.readFile() code to myAwesomeFunction(). When the I/O operation is complete, or errors out, its callback will be placed in the pending queue and it will be processed during the I/O callbacks phase of the Event Loop.

Phase 3: idle / waiting / preparation

This is a housekeeping phase. During this phase the Event Loop performs internal operations of any callbacks. Technically speaking, there is no possible direct influence on this phase, or its length. No mechanism is present that could guarantee code execution during this phase. It is primarily used for gathering information, and planning of what needs to be executed during the next tick of the Event Loop.

In our restaurant example, the chef might start preparing ingredients and equipment needed to prepare the dessert course while the main course is still in the oven. You as a customer don't need to know this is happening, so long as your food is served in the correct order, and in a timely manner.

Phase 4: I/O polling (poll phase)

This is the phase in which all the JavaScript code that we write is executed, starting at the beginning of the file, and working down. Depending on the code it may execute immediately, or it may add something to the queue to be executed during a future tick of the Event Loop.

During this phase the Event Loop is managing the I/O workload, calling the functions in the queue until the queue is empty, and calculating how long it should wait until moving to the next phase. All callbacks in this phase are called synchronously in the order that they were added to the queue, from oldest to newest.

This is the phase that can potentially block our application if any of these callbacks are slow and not executed asynchronously.

Note: this phase is optional. It may not happen on every tick, depending on the state of your application.

If there are any setImmediate() timers scheduled, Node.js will skip this phase during the current tick and move to the setImmediate() phase. If there are no functions in the queue, and no timers, the application will wait for callbacks to be added to the queue and execute them immediately, until the internal setTimeout() that is set at the beginning of this phase is up. At that point, it moves on to the next phase. The value of the delay in this timeout also depends on the state of the application.

In our restaurant analogy you have now received the food and are eating your meal in synchronous order, starting with appetizers and moving on one course at a time. During this process a variety of scenarios may happen. Maybe you decided to order a second main course because you're still hungry. But now you're waiting for the waitress to bring the new dish, so you can eat it immediately before moving on to dessert. Or maybe a dish is taking a long time to prepare and you can't wait any longer. Your internal "timer" is up and you decide to move on and order desert instead.

Phase 5: setImmediate() callbacks

Node.js has a special timer, setImmediate(), and its callbacks are executed during this phase. This phase runs as soon as the poll phase becomes idle. If setImmediate() is scheduled within the I/O cycle it will always be executed before other timers regardless of how many timers are present.

Back to the restaurant example, imagine that you came in for dinner during a rush and the restaurant is full -- you came in during the I/O cycle. Luckily for you, you have a reserved seat. While other people are waiting in standby (setTimeout() callbacks), you are going to your table and making an order (setImmediate() callback).

Phase 6: close events

This phase executes the callbacks of all close events. For example, a close event of web socket callback, or when process.exit() is called. This is when the Event Loop is wrapping up one cycle and is ready to move to the next one. It is primarily used to clean the state of the application.

In the restaurant analogy, this is when you have finished your meal and ask for the bill. You might pay the bill and stay a little longer. During that time another member of your family might come in late and you order more food, going onto the next tick and back to the beginning of the Event Loop. If no one joins you, you pay and exit the restaurant (process.exit()).

To summarize, one tick of the operation cycle of a Node.js application starts with timers. Callbacks of timers for which the wait time is up are executed in order from smallest wait time to largest. After that, I/O callbacks are executed, followed by some internal processing. Then, it is time for the main code to get into the picture and I/O poll queue callbacks are executed. Next, callbacks of setImmediate() and close event callbacks are called. The next tick starts with the timers. This cycle repeats as long as there is code that needs to be executed.

Don't block the Event Loop

Now that we have a fundamental understanding of the Event Loop, we can see why Node.js sends heavy time-consuming operations such as I/O callbacks to the C++ API and its threads. This allows simulation of "multithreading" within a single-threaded Node.js process and allows the main runtime to continue to execute our code without waiting. This gives Node.js the benefits of asynchronous non-blocking I/O interface without being a memory hog.

Looking deeper into the Node.js design documentation we can see that during the Event Loop there are some synchronous methods that are executed together with traditional asynchronous ones that can block the Event Loop in a given phase. Even though Node.js operates with non-blocking I/O, several core modules have expensive API operations. Those modules are Encryption, Compression, File System and Child Process. Those APIs asynchronous methods are not intended to be executed within the Event Loop, and are handed off to the Worker Pool by Node.js.

The Event Loop is what keeps an application running. For example when running a server, the Event Loop is what notices new client requests and directs the creation of responses. This means that all client requests and responses pass through it. Therefore, if at any given time the Event Loop is blocked on the response for any client, current and upcoming clients will not get a response until it has completed processing the blocked request.

Imagine that you are still at the restaurant and ordered food, however, the restaurant has only one waitress and the waitress decided to take a 15-minute break. Nothing happens during that time. The cooks might finish food preparation, but the food gets cold waiting to be delivered. Any new customers are left waiting for someone to take their orders and may leave out of frustration after waiting for too long.

To avoid having frustrated customers -- a Node.js application with a blocked call stack, it is critically important to ensure that all JavaScript callbacks that we write are executed in a timely manner and cannot freeze the application.

When writing your code, monitor the Event Loop metrics such as loop latency and your callback computation score and execution time in order to ensure the entire application isn't blocked by certain pieces of code or APIs.

A good resource is David Hettler's blog post Monitoring Node.js: Watch Your Event Loop Lag! and Daniel Khan's blog post All you need to know to really understand the Node.js Event Loop and its Metrics

Recap

Node.js processes are single threaded in order to avoid the complexity that comes with writing multithreaded code. However, the Event Loop allows offloading I/O tasks to the C++ APIs. That allows the core Node.js runtime to continue running your JavaScript code while the C++ APIs are taking care of the asynchronous I/O operations in the background. This creates an imitation of multithreading and the possibility to write non-blocking code.

The Event Loop contains six main phases: timers, I/O callbacks, preparation / idle phase, I/O polling, setImmediate() callbacks execution, and close events callbacks. After a phase is complete, the application moves to the next tick and all phases are repeated again starting with timers until there is nothing left to process.

Further your understanding

In this tutorial we covered macro-tasks of the Event Loop. We did not cover micro-tasks such as process.nextTick and Promises. Read up on these concepts and research how they fit into the Event Loop.

Additional resources

- Don't block the Event Loop guide (nodejs.org)

- Node.js Event Loop guide (nodejs.org)

Sign in with your Osio Labs account

to gain instant access to our entire library.